This blog, Insulin Pricing in Canada, is part of a series celebrating the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin. You can check out previous blogs in this series, written by CIM Intern Eleanor Medley, here!

In recent years, there has been increasing attention paid to insulin prices. In the U.S., the price of insulin has skyrocketed and there are numerous reports of Americans crossing the Canadian border to get their insulin for one-tenth of the price [1]. In Canada, the cost of insulin for people living with diabetes can vary substantially. You may be wondering, how is insulin actually priced in Canada? The process can seem kind of mysterious (largely because it is), but we will do our best to explore how the cost of insulin in Canada has changed over time, how prescription drug pricing works in Canada, and what this all means for Canadians with diabetes.

Historic Cost of Insulin

Image From: Bresge, Adina. “Frederick Banting Painting Depicts Lab Where Insulin Was Discovered.” Toronto Star, 3 Oct. 2018, www.thestar.com/entertainment/visualarts/2018/10/03/frederick-banting-painting-depicts-lab-where-insulin-was-discovered.html.

Insulin was discovered at the University of Toronto in 1921, so for many years, Canada was a major player in insulin production.

Following the discovery, Connaught Laboratories at the university agreed to produce insulin for Canadians with diabetes. At first, Connaught supplied fairly crude extracts to hospitals to treat severe cases of diabetes at no cost to people with diabetes. Eli Lilly and Co. were also brought in early to help improve and scale up insulin production [2].

In 1923, insulin started to be sold for 5 cents/unit. Assuming the average person with diabetes used 20 units of insulin per day, this meant people spent around $1/day for the first available insulin [3]. While this may not sound like much now, considering the average annual income in Canada at the time was around $500, that was extremely expensive! Banting felt passionate about the accessibility of his discovery though and hoped to bring down the price as much as possible [3]. Connaught Labs did not engage in commercial business, so the price they charged for insulin exclusively depended on the costs of production [4].

As Connaught was able to expand its facilities and improve production, the price of insulin steadily dropped. In 1936, Connaught introduced longer-acting protamine zinc insulin, and the price of regular insulin continued to fall to 20 cents/100 units in 1942 [3]. This price remained stable in Canada until 1967.

Image from: Tasker, John Paul. “Vaccine Envy: Why Can’t Canada Make COVID-19 Doses at Home?” CBC, 28 Apr. 2021, www.cbc.ca/news/politics/domestic-vaccine-manufacturing-canada-1.6004427.

In 1950, NPH insulin was introduced. The higher cost of NPH offset the costs of regular insulin and protamine zinc insulin, keeping their prices steady. The economic boom at this time made insulin more affordable in Canada than it had ever been [3].

Throughout the fifties and sixties, Connaught significantly increased insulin production and export. They also introduced Lente insulin at a comparable price to NPH and later another variation, sulfated insulin, at a significantly higher price [3].

After remaining stable for years, mounting economic pressures made Connaught raise the prices of regular and protamine zinc insulin by approximately 10% and 20% respectively in 1967. By then, most of Connaught’s insulin patents had expired, and they were no longer gaining royalty income [3].

Connaught Labs was sold to the Canadian Development Corporation in 1972 and eventually became privatized in 1986 [5]. There was a spike in the price of beef and pork pancreas in 1974, causing Connaught to increase their insulin prices again throughout the mid-to-late seventies [3].

Adapted from Table 1, Rutty, “Couldn’t live without it”: diabetes, the costs, and innovations of insulin in Canada, 1922-1984 (2008), Bank of Canada Inflation Calculator.

In 1980, Eli Lilly and Co. were granted permission to sell their version of insulin, called “iletin”, in Canada. The development of synthetic insulin made through recombinant DNA technology was also underway, marking a new era of human insulin. By 1984, insulin production fell out of Canadian control [3].

Today, the “Big Three”–Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi–control 99% of the global insulin market value and 96% of volume [6]. The legacy of Connaught Labs can now be found at Toronto’s Sanofi Pasteur Canada Connaught Campus [7].

Since human insulin was genetically modified to be rapid or long-acting in the late 90s, these more expensive analogue insulins have come to dominate the market. In recent years, the increased use of newer long-acting insulins such as Lantus and Levemir has contributed to the rapidly increasing cost of diabetes treatment in Canada [8].

Adapted from Alogliptin Plus Metformin (Kazano) for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2015 Aug. Table 3, Cost Comparison of Insulin Drugs. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK349224/table/T63/

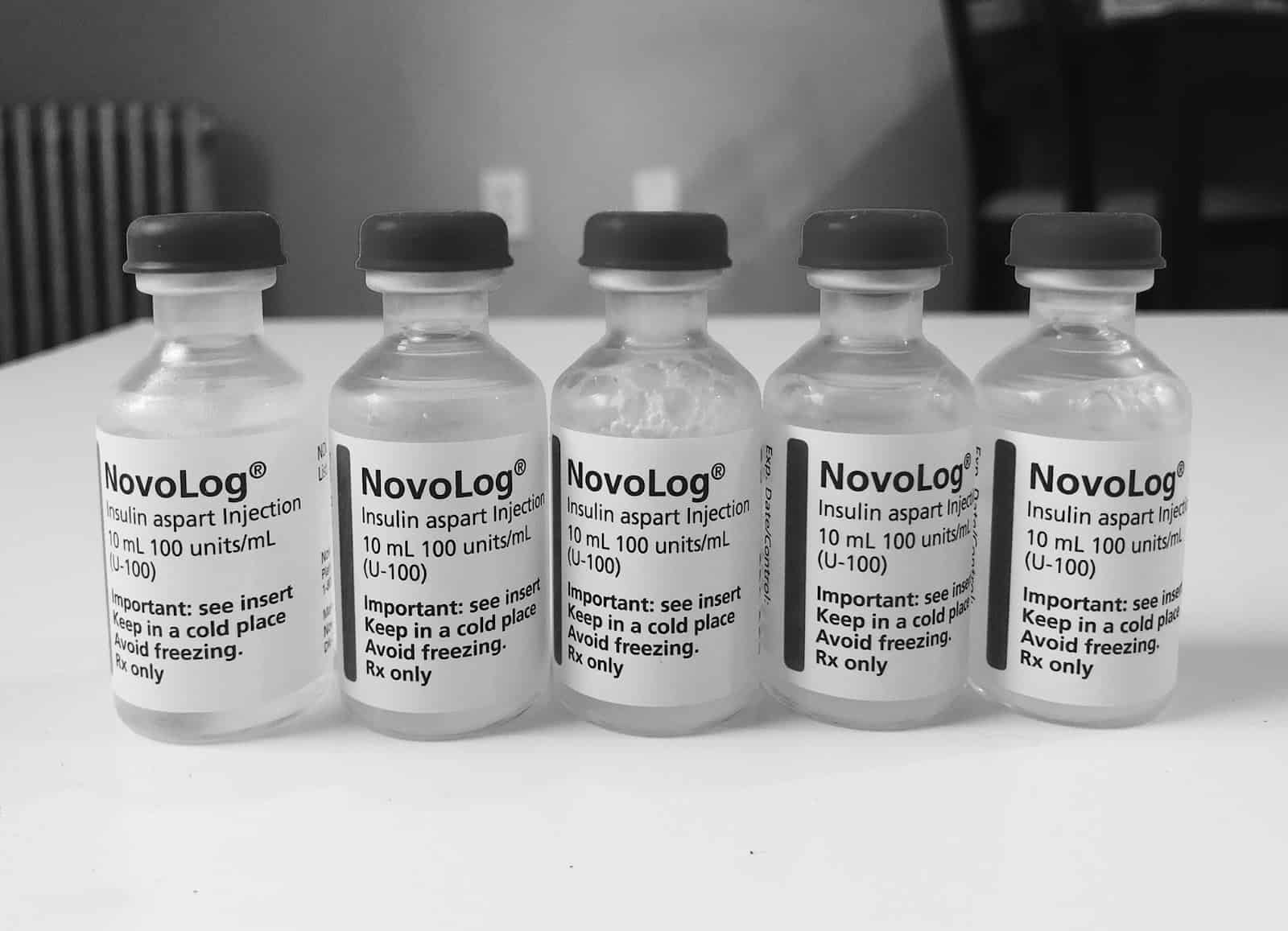

As of 2020, in Ontario, it costs approximately $35 for a 10 mL vial of Insulin-Toronto (regular insulin) or Humalog (100u/mL), and $75-80 for 10 mL vial of Lantus (100 u/mL) over-the-counter.

Overall, the price of insulin depends greatly on its formulation. While the cost of regular insulin dropped in the years after its discovery and has managed to remain relatively low, newly introduced insulins have historically been more expensive.

Pharmaceutical Supply Chain

So how do new types of insulin get from the lab and into the hands of someone living with diabetes in Canada? The process has four stages:

Made from “Canada’s Drug Supply Chain.” Canada.ca, Government of Canada.

First, drug companies submit scientific evidence demonstrating the safety, efficacy, and quality of their product to Health Canada. Once authorized for sale, the drug is then manufactured for use. Next, the product goes into distribution. Drug manufacturers can either distribute the drug to hospitals and pharmacies directly or go through group purchasing organizations and wholesalers. Finally, people receive the drug from their health care provider or pharmacy. If the cost of the drug is covered by insurance, the pharmacy is reimbursed by the insurance company after the medication is dispensed [9].

Insurance Coverage for Prescription Drugs

Under Canada’s publicly funded universal health care system, Medicare, all Canadian residents have access to “medically necessary hospital and physician services without paying out of pocket”. Health care insurance plans are administered by the provincial and territorial governments [10]. Canada is considering implementing a National Pharmacare program that would standardize prescription drug coverage across the country, but for now, prescription drug coverage varies by province/territory.

After Health Canada has approved a new drug for use in Canada, provinces and territories decide if the drug will be eligible for reimbursement under their public drug plan. This decision-making process happens through the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) Common Drug Review (CDR). The CADTH evaluates the clinical and economic evidence of the drug and then provides recommendations to Canada’s public provincial drug plans (excluding Quebec) [11].

All provincial drug plans have insulin coverage, but coverage for different insulin formulations varies [12]. Some provinces also have specialty programs to help provide other diabetes supplies such as insulin pumps, often for specific populations like seniors and youth.

In Ontario, the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care has an Ontario Drug Benefit Plan (ODB) that can help cover the cost of insulin for people with diabetes on a provincial social assistance program and for those who are 65 or older. Cost-sharing with individuals under this plan depends on annual income level. There is also the Trillium Drug Program in Ontario which helps cover the cost of insulin for people whose drug costs are high compared to their annual income (more than 4%). For most people, the deductible equals approximately 4% of the household income after taxes, and once coverage begins the beneficiary pays $2 for each drug that is filled [13]. You can read more about similar plans in other provinces here.

In addition to public coverage, approximately two-thirds of Canadians have complementary private insurance that can help cover the cost of prescription drugs like insulin and other diabetes supplies [14]. It is also important to note that in Canada, you can purchase insulin without a prescription.

Of all insulin spending in Canada in 2015, 52% was paid for publicly, 37% was paid for privately, 8% was paid for with cash, and 2% was paid for by non-insured health benefits [12].

Adapted from Figure 1, Xu et al., Analysis of Trends in Insulin Utilization and Spending Across Canada from 2010 to 2015.

Regulation of Drug Prices

PMPRB

One way that Canada maintains the cost of insulin is through something called the Patented Medicines Prices Review Board (PMPRB). PMPRB was established in 1987 and amended in 2019 (though the implementation of these amendments has been delayed) [15]. In a nutshell, the PMPRB ensures that patented drug prices are not “excessive” [16]. To do so, the board considers a product’s therapeutic benefits relative to existing comparable drugs, consumer price index changes, and the price of the drug in a group of reference countries [17]. The board also reports trends in pharmaceutical sales and pricing for all medicines [16]. The 2019 PMPRB amendments include analyzing new factors such as cost-effectiveness, changing the group of reference countries to be more comparable to Canada, and changing reporting requirements [18].

![PMPRB Reference countries before and after the proposed 2019 reforms. Before: France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, UK, Switzerland, and the U.S. After: France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, UK, Australia, Belgium, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain [19]](https://www.connectedinmotion.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/unnamed-15.jpg)

The PMPRB has limitations, though. For example, it only regulates the “factory gate price” of prescription drugs or the price that patent holders charge wholesalers, hospitals, or pharmacies for their drug. The factory gate price is not the price that a person actually pays at a pharmacy (recall the pharmaceutical supply chain outlined above). The final price depends on how much wholesalers and retailers mark up, how much pharmacists charge for filling the prescription, and how much insurance is willing to cover [15]. The “hidden costs” contributing to the total prescription drug cost are very hard to analyze due to lack of transparency in the industry and variability between province, payment plan, and drug type.

Adapted from Thériault, Louis. “Pharmacy Markups.” The Conference Board of Canada, 26 Apr. 2017.

For example, pharmacy markups were established to cover distribution and inventory carrying costs for pharmacies and they differ by province [20]. In Ontario, the markup for all Ontario Drug Benefit high-cost claims greater than or equal to $1,000 is 6% and the markup for claims less than $1,000 is 8%. For non-insured health benefits, the price will generally be the same as the respective provincial formulary.

Most drugs are delivered through wholesale, so pharmacies also have to pay the wholesaler an upcharge. To further complicate things, there are also “middlemen” Pharmacy Benefit Managers such as Telus Health and Express Scripts Canada that manage prescription drug plans for insurers and their members [21].

Another limitation of the PMPRB is that it only regulates the price of patented drugs (it’s the first ‘P’ in PMPRB) [22]. Patents are expiring on many varieties of insulin, and “biosimilar” versions have started being released as alternatives [23]. Like generic versions, biosimilars are usually cheaper than the original drug. It is generally thought that increased competition from biosimilars will increase insulin accessibility globally [24].

Finally, the PMPRB drug price is largely considered “a ceiling price from which to begin negotiation, rather than a means to achieve lower prices” [25]. So how does Canada actually negotiate for lower drug prices?

pCPA

The pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA) is another way that Canada determines the cost of insulin. Established in 2010, the pCPA “conducts joint provincial/territorial/federal negotiations for brand name and generic drugs in Canada to achieve greater value for publicly funded drug programs and patients” [26].

In a more unified approach, the pCPA seeks to increase access to lower-cost drugs consistently across all jurisdictions. The pCPA negotiates confidential prices directly with manufacturers, then all participating drug plans receive the discount.

Unlike the PMPRB, the pCPA negotiates the price of biosimilar and generic drugs as well as patented brand names [26]. In February 2020, the pCPA completed negotiations for Basalgar, Toujeo, Fiasp, and Tresiba insulins [27].

However, Canada pays some of the highest generic drug prices in the world. In 2006, Ontario started regulating the practice of pharmacies paying or receiving rebates/kickbacks in exchange for stocking particular generic drugs to try to curb the high prices. In 2013, the province banned the practice altogether. Despite this, Canada still has the second-highest generic drug spending per capita among OECD countries (behind only the U.S. [28]) and there are suspicions this may be due to persisting underground kickback schemes [29].

Conclusion

While regulation by various bodies prevents insulin prices in Canada from reaching American heights, the cost of insulin that Canadians with diabetes actually bear varies significantly by province, insurance coverage, and pharmacy [30].

Furthermore, alterations in insulin formulation and the introduction of new types of insulin have caused costs to rise significantly. The PMPRB is limited to setting the factory gate price of patented drugs, while the pCPA can negotiate the price of brand name and biosimilar insulins across Canada.

In the future, increased transparency in the pharmaceutical supply chain, increased competition in the insulin market, implementation of the PMPRB reforms, and the introduction of a National Pharmacare plan could make access to insulin in Canada more affordable and equitable.

Without sufficient coverage, the cost of insulin is a significant burden—there are reports of some Canadians paying over $1500/year for insulin out-of-pocket [31]. High costs of insulin and accompanying diabetes management supplies can have extremely dangerous consequences for people living with diabetes.

SOURCES

- Goldman, Dr. Brian. “The Soaring Cost of Insulin.” Dr. Brian’s Blog, CBC Radio, 28 Jan. 2019, www.cbc.ca/radio/whitecoat/blog/the-soaring-cost-of-insulin-1.4995290.

- Louis Rosenfeld, Insulin: Discovery and Controversy, Clinical Chemistry, Volume 48, Issue 12, 1 December 2002, Pages 2270–2288, https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/48.12.2270

- Rutty CJ. “Couldn’t live without it”: diabetes, the costs of innovation and the price of insulin in Canada, 1922-1984. Can Bull Med Hist. 2008;25(2):407-431. doi:10.3138/cbmh.25.2.407

- Rutty, Christopher J. “Connaught Laboratories & The Making of Insulin.” Connaught Fund, connaught.research.utoronto.ca/history/article3/.

- Tasker, John Paul. “Vaccine Envy: Why Can’t Canada Make COVID-19 Doses at Home?” CBC, 28 Apr. 2021, www.cbc.ca/news/politics/domestic-vaccine-manufacturing-canada-1.6004427.

- Beran D, Hirsch IB, Yudkin JS. Why Are We Failing to Address the Issue of Access to Insulin? A National and Global Perspective [published correction appears in Diabetes Care. 2018 Jun 15;:]. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(6):1125-1131. doi:10.2337/dc17-2123

- Rutty, Christopher J. “A History of Connaught Laboratories.” Connaught Fund, connaught.research.utoronto.ca/history/.

- “The Use of Diabetes Drugs in Canadian Public Drug Plans.” Canada.ca, Government of Canada, 18 Apr. 2016, www.pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca/view.asp?ccid=1244.

- “Canada’s Drug Supply Chain.” Canada.ca, Government of Canada, 9 May 2014, www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/drug-shortages/canada-drug-supply-chain.html.

- “Canada’s Healthcare System.” Government of Canada, Health and Human Services, 22 Aug. 2016, www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canada-health-care-system.html

- “CADTH Common Drug Review (CDR).” CADTH.ca, 23 July 2018, cadth.ca/about-cadth/what-we-do/products-services/cdr.

- Xu Y, Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, Cadarette SM, Tadrous M. Analysis of Trends in Insulin Utilization and Spending Across Canada From 2010 to 2015. Can J Diabetes. 2019;43(3):179-185.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jcjd.2018.08.190

- Diabetes Canada. Provincial and Territorial Formulary Chart, Diabetes Initiatives Comparisons by Province. https://www.diabetes.ca/DiabetesCanadaWebsite/media/Advocacy-and-Policy/Provincial%20and%20Territorial%20Formulary%20Chart/Provincial-Comparisons-2018.pdf; Ontario government. Health Coverage: Helpful Options for People with Diabetes, Health.gov.on.ca; “Get Help with High Prescription Drug Costs.” Ontario.ca, Ontario Government, www.ontario.ca/page/get-help-high-prescription-drug-costs. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/diabetes/docs/diabetes_factsheets/English/Coverage_21july09.pdf

- Eising, Martin. “Health Insurance Coverage For Diabetics.” Insurance-Canada.ca, 2 Nov. 2018, www.insurance-canada.ca/2018/11/02/healthquotes-diabetes-coverage/.

- “Government of Canada Announces Changes to Lower Drug Prices and Lay the Foundation for National Pharmacare.” Canada.ca, Government of Canada, 9 Aug. 2019, www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2019/08/government-of-canada-announces-changes-to-lower-drug-prices-and-lay-the-foundation-for-national-pharmacare.html; Reguly, Teresa et al. “Pause on PMPRB Reform: Implementation of New Pricing Regulations Delayed to 2021.” Torys.com, 2 June 2020, www.torys.com/insights/publications/2020/06/pause-on-pmprb-reform.

- “About PMPRB.” Canada.ca, Government of Canada, 18 Apr. 2018, www.pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca/about-us.

- Menon, Devidas. “Pharmaceutical Cost Control In Canada: Does It Work?” Health Affairs, vol. 20, no. 3, 2001, pp. 92–103., doi:10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.92

- Health Canada. “Notice on Proposed Amendments to the Patented Medicines Regulations.” Canada.ca, Government of Canada / Gouvernement Du Canada, 9 Aug. 2019, www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/programs/notice-consultation-regulations-patented-medicine.html.

- Camenzind, Alexander, and Cole Meagher. “PMPRB Shakeup – United States and Switzerland No Longer Relevant Countries.” Gowling WLG, gowlingwlg.com/en/insights-resources/articles/2019/pmprb-shakeup-united-states-and-switzerland-no-l/.

- Thériault, Louis. “Pharmacy Markups.” The Conference Board of Canada, 26 Apr. 2017.

- Bonnett, Chris, and Denise Balch. “PMPRB Draft Guidelines Consultation.” 24 Feb. 2020.

- “Frequently Asked Questions | Patented Medicines Review Board.” Welcome, 18 Apr. 2018, www.pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca/about-us/frequently-asked-questions/.

- Rotenstein, L. S., et al. “Opportunities and Challenges for Biosimilars: What’s on the Horizon in the Global Insulin Market?” Clinical Diabetes, vol. 30, no. 4, 2012, pp. 138–150., doi:10.2337/diaclin.30.4.138.

- Lash, Robert, and Andrew Mulcahy. “Will More Biosimilar Agents Help Lower the High Cost of Insulin?” Healio, Endocrinology, 2019, www.healio.com/news/endocrinology/20190916/will-more-biosimilar-agents-help-lower-the-high-cost-of-insulin.

- Husereau, Don, et al. “Evolution of Drug Reimbursement in Canada: The Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance for New Drugs.” Value in Health, vol. 17, no. 8, 2014, pp. 888–894., doi:10.1016/j.jval.2014.08.2673.

- “The Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance .” Canada’s Premiers, 29 Apr. 2020, www.canadaspremiers.ca/pan-canadian-pharmaceutical-alliance-archives/.

- “The Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (PCPA): Negotiations Status Update.” PDCI Market Access, 4 May 2018, www.pdci.ca/the-pan-canadian-pharmaceutical-alliance-pcpa-negotiations-status-update-18/

- Mikulic, Matej. “Generic Drug Spending per Capita OECD 2018.” Statista, 25 Sept. 2019, www.statista.com/statistics/859350/generic-drug-spending-oecd/.

- Sawa, Timothy, et al. “’Greed Is a Powerful Weapon’: Are Illegal Kickbacks in Ontario Driving up the Cost of Your Generic Drugs? | CBC News.” CBCnews, CBC/Radio Canada, 13 Jan. 2019, www.cbc.ca/news/health/pharmaceutical-drugs-rebates-ontario-1.4952256.

- Abedi, Maham. “‘This Is a Solvable Issue’: Pricey Insulin Has Americans Trekking to Canada in ‘Caravans.’” Global News, 9 May 2019, globalnews.ca/news/5249662/americans-driving-canada-insulin-prices/.

- Adhopia, Vik. “The Staggering Cost of Type 1 Diabetes: It’s Not Just about Insulin | CBC News.” CBC News, 2 Apr. 2019, www.cbc.ca/news/health/type-1-diabetes-insulin-costs-1.5079939.