This blog is part of the Living Without Limits series featuring conversations with CIM community members who engage in fun, challenging, and adventurous activities and careers. This post highlights Autumn Watkinson who does land restoration and restoration ecology fieldwork with type 1 diabetes.

Eleanor: First, could you tell me a little bit about your diabetes story?

Autumn: I was diagnosed in 1996, so I’ve had diabetes for 25 years now. I was really lucky because I had a care team and family that really encouraged me to live life without limits. There was nothing that was off limits for me, which facilitated me working in the career that I’m in now.

I currently use the Medtronic 670g pump with a CGM (Guardian sensor). That’s been working wonderfully for me because it helps moderate the effects of stress, which I seem highly susceptible to, and any spikes or dips in my BG because of my unpredictable schedule. In my career, every day ends up being very different, so having a pump that can adapt to that helps a lot.

How do you describe what you do and what kind of research you’re involved in?

If I’m being official, my title is “postdoctoral research and teaching fellow”. I have a PhD in Land Reclamation and Remediation, which is an environmental science. I currently teach environmental science courses at the University of British Columbia and conduct research into fixing anthropogenic or human-made disturbances in ecosystems. My work in the past has generally focused on habitat restoration, which centers on creating habitat for species at risk and other species of concern. On a daily basis, that could mean e I’m reading scientific papers and reports, writing reports or manuscripts, visualizing and analyzing data, conducting field work, planning experiments, planning courses, and/or teaching!

What made you interested in land reclamation and environmental sciences?

Growing up, we lived in the country so I was outside all of the time. If we weren’t doing something inside like homework or housework, my mom wanted us outside. If you’re in nature that much, you end up loving it and having an appreciation for it. I’ve always loved science and solving problems. For a while I thought I would go into a medical field, and I think having diabetes influenced that. I started university in biomed, but switched over to ecology and evolution halfway through, and that’s when things really clicked for me. Especially after going into the field! Field work is one of my favorite things.

Could you describe what doing fieldwork is like for you?

Field work is a huge component of what I do. You can do experiments in the lab, but you have to verify your findings in the field because, in land reclamation, what’s the point if it’s not going to work once we apply our methods in nature? ? Field work usually starts by taking surveys of the area you plan to work in – that can mean a lot of hiking, especially in remote areas where there may not be road access. After finding representative areas, we set up our experimental or monitoring plots. But after that, most of the work is hiking into our plots and then looking at a lot of plants!

Field work for environmental sciences can lead you to some remote locations which can be tricky as a diabetic. For example, during my PhD I was in Grasslands National Park, a remote area with no cell reception and some extreme weather and animals. In a prairie ecosystem, you’re often working in extreme heat, so there will be days when it’s almost 40 degrees celsius and there’s no shade. You need to find ways of keeping your insulin cool enough in the day. Being in a remote location, you need to carry a satellite radio to call for help if needed, but even if someone can come, it might take them a really long time to get there. So you need to be prepared to manage worse case scenarios on your own and be confident in your field crew to help you.

There are all of these layers that are difficult enough for someone without diabetes to deal with, but when you then start dealing with diabetes in these conditions, you can imagine it gets really challenging.

What special considerations do you have to make when doing fieldwork with type 1 diabetes?

Planning for the heat, you need to make sure that your insulin pump isn’t going to heat up too much in the direct sun. I use a little FRIO pack that you can clip your pump into on your belt. We have a research house where I can keep my insulin cold when I’m not using it.

There’s a lot of prep work that goes into making sure your team knows exactly what to do if you need them to do it. We do that for everyone. For example, we had a girl with a lung condition on our team and also had a plan laid out for her. It’s really good to have an employer and team that will do that for everyone. I never felt like an exception in that way.

It can be scary knowing you’re somewhere so remote. I get ketones easily, but normally I can feel it coming on and deal with it. But I had one incident where I was out in the field and woke up at 3 am and immediately started throwing up. My blood sugar was 28 mmol/L and I felt so out of it I couldn’t administer insulin through a syringe or change my site. I had a 2 hour ambulance ride and then a 5 day stay in the hospital with DKA. When you’re in a location where people don’t know you, and you don’t have your care team, a hospital stay that would normally be half a day can become longer. I’m not trying to scare anyone, but the reality is that even when you do your best, there is a lot out of your control and you have to rely on the people around you. Luckily, I had people around me that knew I had to get to the hospital. But it was an eye-opening experience for me, because even when I got to the hospital, the ER doctors had no idea what to do with me.

That sounds scary–Do you have any advice that you learned through that experience?

One thing I learned was to always have a card or sheet with you with your evacuation plan and safety information written out in detail. In an emergency, sometimes people panic so having all of it written out instead of just prepping people verbally is helpful. Making sure everyone you work with knows where that sheet is is important. The information sheet is not just useful for your team, but also for the doctors that will be treating you. I’ve had emergency doctors try to give me an obscene amount of insulin (for me) because there’s no way for them to know the differences between people’s treatment. I write out things like, “I use a Medtronic 670g insulin pump and CGM. Do not deliver a bolus or take my pump off.” I also write out my carb ratios, my sensitivity factors, what BG I correct to, and what kind of insulin I use. My care team information is also on there and at the very top, I put my partner’s name who I identify as my diabetes advocate. Having someone to advocate for you and explain what you need is very important, whether it’s your parents, your partner, your friend, or anyone that is super familiar with how you manage your diabetes.

Have you ever experienced any pushback or stigma associated with working in the field with diabetes?

Because of all the things that can happen, and with a lot of people being unfamiliar with diabetes, I’ve had pushback from a few people. But nothing too overt. No one has strictly said “No, you can’t do that because you are diabetic.”

I’ve ended up in the hospital in the past and get ketones every now and then, and that’s something I’m used to. It’s a risk I’m willing to take with my management to live the life I want to live and have this career. But to then have people you work with also accept that risk as well…it can take a bit of time for them to get comfortable. They have to accept that when I’m doing this meaningful work, there is a risk that something could happen to me and it wouldn’t be their fault. I think they believe that if I go out into the field and something happens, as my supervisor they would be to blame. I don’t feel that way, as long as we do everything we can to prevent it. We always have a safety plan and evacuation plan.

After that one incident when I was taken to the hospital from the field, my supervisor was really worried about me going back to work. With diabetes, we know that we can bounce back from low or high blood sugars pretty quickly. But she couldn’t understand that because she hadn’t experienced it before. There was a bit of pushback there, but I convinced her and she trusted me. I think it’s just about developing trust and a meaningful relationship with people.

For me, what’s worked is letting people know how I manage things, but also letting them see that in action. It’s one thing to tell them, but it’s another to actually let them into my life and let them see it. Once they can see that sometimes I just need a quick rest and then am totally fine again, that starts to foster trust and confidence. If I go low on a work call, I’ll just say, “I’m just going to sip this juice box while we talk”, and then they can see that in 15 minutes, I’m all good again.

Other than that, I’ve had a lot of people actually look at me and the career I chose knowing I’m diabetic and say, “Oh wow, that’s amazing, good for you”. They think it’s more of an attribute than a risk, and that’s lovely! Part of it is letting people in and showing them you can still be out in the field and good at what you do with diabetes.

Sometimes I worry about telling people too much because I don’t think people understand how much my blood sugar actually fluctuates throughout the day. I like that you demonstrate to people how you manage your diabetes by letting them in.

I still struggle with that too. I try to email my boss and explain, for example, “I’m going to be offline this morning because I had lows all night and I just need the morning to recover.” I’m trying to strike that balance. As long as I follow through with what I say I need to do, then they can start to trust that. Some people still might not believe you, or they might think you’re trying to be brave and encourage you to take the whole day off when you don’t really need that. Also when you start to let people in more and show them your blood sugar fluctuations, there can be comments with a “why aren’t you better at this” kind of tone. But it usually gets better the more they learn about it. Then they start to find out this is normal and that I’m doing well with diabetes.

Do you know anyone else with diabetes that does research similar to you, or that you’ve been able to talk to about the unique situations you work in?

When I was at the University of Alberta doing my PhD, I felt extremely isolated and alone in it. That’s when I really started to want community and support. I found CIM through googling, and the Adventure Team was one of the first links. I saw that one of the participants, Anissa Gamble, was also a graduate student at the University of Alberta. So I emailed her and we met up. It was lovely to meet someone else who was a grad student with diabetes. I hadn’t met anyone else who had done that, so that was refreshing in and of itself. I think a lot of her work took place in a laboratory, so although we could share a lot of graduate school experiences with the admin, stress, and exams, the actual experiences being in the field vs. in the lab were very different.

Other than that, I haven’t met any other graduate students with diabetes, though I’m sure they’re out there. I’m hoping this story might help reach them and foster a mini community within CIM of people who do field work!

I was involved with lab work in the past, and I also felt isolated. I found lab work so difficult with diabetes because once you start an experiment, you can’t really leave it to take a break and address your blood sugars.

I had never really felt isolated with my diabetes before that and I’m wondering if it’s because that was the first time I started to see differences in my experience vs. other people’s experiences. You were also facing a unique challenge other people didn’t know you were experiencing. That hits hard, when other people can’t see your reality. It’s so nice to be in a community that understands your journey and what your day-to-day is like.

With field work, there’s nothing running that I can’t step away from for a second. The plants aren’t going anywhere, so I can come back and measure them when my blood sugar is up again. With lab work though, it’s a different story. It’s tricky because you can’t have food in laboratories, so you have to carefully manage when you’re going in and out. In some circumstances, like you said, you can’t leave your experiments unsupervised. But it’s also unrealistic to work with a partner all day because you don’t really need them all of the time. Even just the challenge of taking all of your PPE off and getting food from a locker that might be far away when you’re low, there’s so many things to think about. I used to try to communicate with the lab manager about keeping a juice box and snack in a labeled container right by the door and they were totally fine with that as long as it didn’t impede lab safety.

Did you do an Adventure Team trek with CIM?

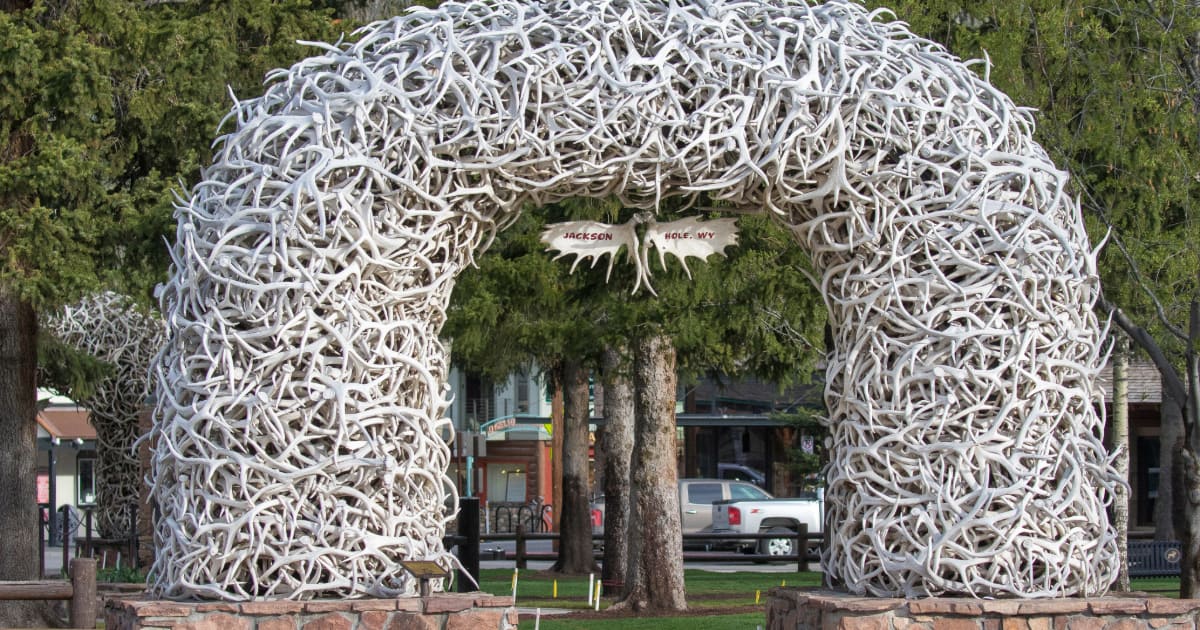

Gamble encouraged me to apply to Adventure Team and it was so serendipitous because the applications were due like 2 days after we had met! But I applied and was chosen for the 2018 team. We were supposed to do the Rockwall Trail, but there were fires so we did some hikes in Jasper and Banff that were beautiful.

Did being involved with Adventure Team give you any transferable skills or knowledge for doing fieldwork with type 1 diabetes?

It helped me gain confidence. I learned about other people’s management styles which was lovely because looking things up on the internet is not the same as actually talking to people. I talked to people like Tina Sartori who was managing her diabetes very differently than I was – with more emphasis on diet – that she found very successful, so I adopted some of that which helped me a lot.

I used to be a person who thought I had to take a ton of juice boxes wherever I went which made hiking way more difficult because it was weighing me down! When the Adventure Team showed me how to manage lows with lighter weight snacks, I was a little scared because it wasn’t my usual. But I put trust in Jen and the CIM team because they know what has worked in the past for themselves and a ton of other diabetics. That was really eye opening for me and made me way more efficient in the field. I was always trying to prepare for having a really bad low, and I’m still prepared for that, but there’s other ways: evacuation plans, relying on the people with me, carrying different snacks, and closely monitoring my blood sugar.

Another thing that was really eye opening for me was preparing for exercise with food. It sounds weird that I didn’t do that before because I played sports and was always active. I think it’s because growing up, I was told diabetes shouldn’t get in your way or limit you. And what I took away from that as a kid and rebellious teen who ignored their diabetes for a long time, was that I could do whatever I want, which was what everyone else was doing (i.e. not preparing for exercise with food, or testing their blood sugar). I was often too dehydrated and having leg cramps or going low because I wasn’t eating the right combination of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats to sustain me through activity. Seeing people actively do that without begrudging it on the trek changed my perspective. Even though I liked to think I was very open about my diabetes, I was still slightly in denial and angry about it, and the trek helped me accept it a lot more.

I feel like my doctors were always talking about how to use insulin to compensate for what I was eating, but never how to eat in order to help my blood sugars. I’m learning that later in life.

That’s so true for me, too! I wonder if it was because of being diagnosed in the late 90s? When I moved to Alberta in 2016, that was really the first time that my management team started talking to me about nutrition in that way (i.e. you can’t just eat what you want and expect things to be fine even if you have insulin), and it helped immensely.

What is your favorite thing about your job?

As much as I’m talking about things that can go wrong, so many things can go right! It can be so affirming and beautiful once you’re prepared and can let it all go. Knowing I don’t have to worry about diabetes any more than usual because everyone’s all prepped, it just frees me up to enjoy my work.

What I really enjoy is working on a problem with a real-world application. I find enjoyment in every little part of it because it contributes to that larger, overall goal. In the field in particular, I enjoy being outside and being able to do something that benefits nature. I enjoy nature so much personally and want future generations to be able to enjoy it. Not only because we need functioning ecosystems for humans to thrive on the planet, but also because being outside and being in nature is such a beautiful experience.

I’m kind of a perfectionist and it gets in the way of diabetes so much because you’re never going to have perfect blood sugars day in and day out. I’ve had to let the perfectionist mindset go a bit. Applying that adaptability in my field work, too, has been helpful. You can look at your body as a dynamic system that you have to adapt to in your diabetes management. Ecosystems are the same: when they’re recovering from disturbance it’s similar to when your body recovers from a sickness. Learning to be resilient when I have setbacks in diabetes has helped me succeed in science too.

Is there anything you’d like to say to people living with diabetes who may be feeling hesitant to pursue certain interests they have?

Something I’d like to say to young people interested in field work is, go for it! You’re not limited, you can do it. You might get pushback, but there’s definitely ways to deal with that. Let people who need to know more about it. They care about you and don’t want anything to happen, so give them proof it will be okay. You can also start slow–get out there and maybe do some hikes with a group of people. And always feel free to reach out to the community!

What is the best way for people to get in touch with you if they want to talk more?

If anyone wants to reach out to me about science or diabetes, or CATS (I have 3), I would be happy to chat. You can email me at autumnly@ualberta.ca

Autumn’s Top Tips for fieldwork with diabetes!

- Bring more diabetic supplies than you think you’ll need (sweat makes infusion sites and CGM tape peel off – consider purchasing tape to help keep sites on)

- Bring back up supplies in case your pump or CGM fails (syringes, glucometer)

- Charge your devices and bring charging equipment – consider purchasing a solar-powered charger for remote work

- Have an evacuation plan and write out steps for evacuation in the order in which they should be executed. Include directions to the nearest hospital and emergency numbers

- Have a ‘Diabetic Emergency’ cheat sheet for your team – prep everyone for what they should do in case of emergency and tell them where the sheet is (people might panic in emergencies so having it written down is helpful)

- Carry a sheet with your diabetes care instructions on it in case you need to be taken to the ER. Include insulin type, pump type, carb ratios, sensitivity factor, how much long-acting insulin you would need if your pump needs to be removed. Identify a diabetes advocate at the top of the sheet and instruct doctors to call them if you’re admitted. Include numbers for your diabetes care team.

- Keep your insulin cool in hot weather: FRIO packs work well for insulin pumps; ice and coolers also work well for stored insulin

- Keep yourself hydrated in hot weather – understand how heat and cold affect your blood sugars and prepare for this

- TRUST that you have prepared well and ENJOY!