In order to better understand the world we live in, we must look to where we have been. This 3-part Diabetes Past & Present series will examine different elements of diabetes in history and discuss how these stories relate to current events in the community. We’ll start by looking at the history of insulin.

But first, a little bit about our author:

Hello there! My name is Eleanor, and I will be starting to write for Connected in Motion’s Fresh Air Blog, so I thought I would introduce myself!

I recently joined CIM as a Content Intern. As someone who has been a fan of CIM programming for a little while now, I’m very excited to join the community. After months of Instagram stalking, I finally attended my first event this past spring, the U.S. Virtual Slipstream (at least one good thing came out of this pandemic!). I learned so much from the event, and I’m eager to be a part of the behind-the-scenes work at CIM.

I was diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes at the age of four. I went to diabetes camp for a few summers as a kid, but failed to find a diabetes community after that. CIM has provided a place for me to connect with other adults with diabetes.

I was born and raised in the Boston area and this year, I graduated from the University of Toronto where I studied Biochemistry. In the fall, I will be attending graduate school for public health. My professional interests lie in studying how the environment affects human health. I hope for my CIM content to incorporate elements of scientific research and public health advocacy. I’ve also become interested in understanding diabetes history lately, so you will see some blog posts about that! In addition to sharing personal thoughts, I would also like to shed a light on real experiences of people from all walks of life living with diabetes, expanding the narrative typically present in the media.

In my free time, I love listening to music and podcasts! I also really enjoy being outside, especially close to water. You can often find me on a stroll with my dog catching up on the latest tunes.

I wish I could say that when my pancreas quit on me all those years ago, I said ‘thank you, next’ and decided I was better off without it. Insulin? Who needs her? Wait–I do. And it isn’t just me with the co-dependency problem! We all do.

That precious clear liquid is a literal lifeline for people with diabetes. Thanks to a team of Toronto scientists—Frederick Banting, Charles Best, John Macleod, and James Collip—discovering insulin in 1921, folks diagnosed with diabetes could begin to survive and thrive. So, after almost 100 years, what has changed about insulin manufacturing, and what types of insulin are available now? In the first instalment of this series, I will tell the story of this landmark medical discovery and use it as context to discuss more recent developments in insulin.

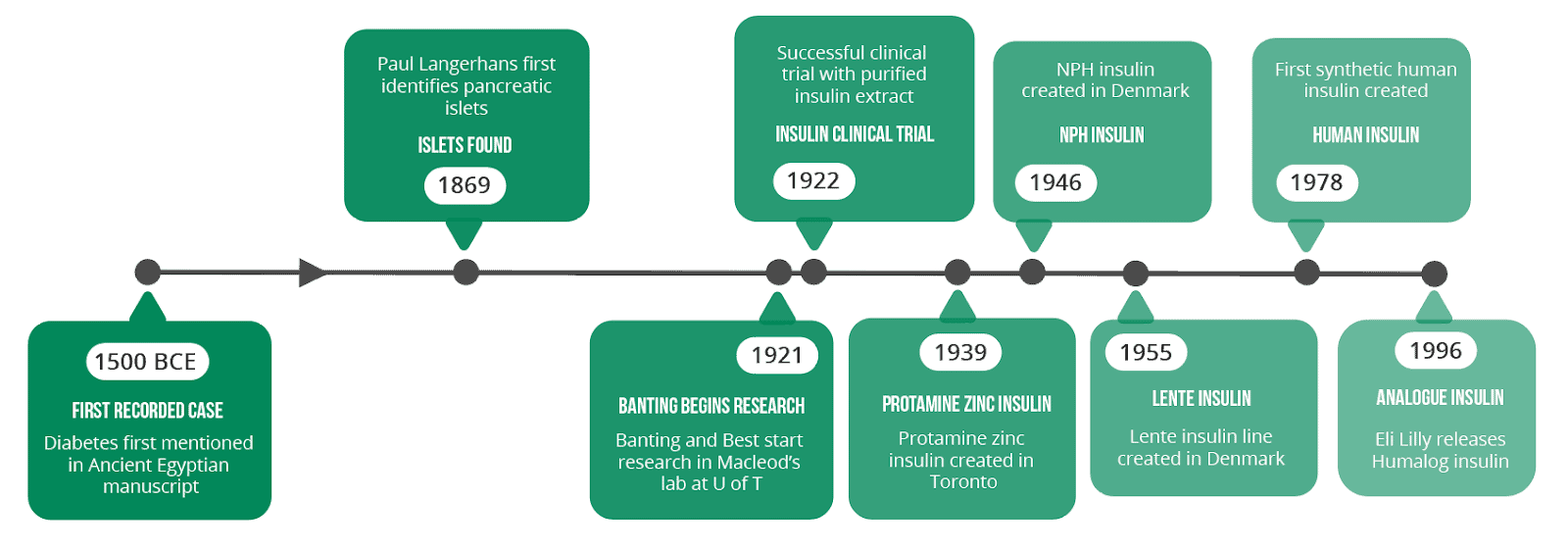

First, I need to set the stage about what it was like to have diabetes before insulin was discovered. Bear with me, this was a bad time for people with diabetes. If we’re going all the way back, the first recorded mention of diabetes that we know about was in an Egyptian manuscript from 1500 BC [1]!

Diabetes was initially characterized as “too great emptying of urine” that tasted “sweet like honey” [2]. How did they know what the urine tasted like, you ask? Well, Indian physicians knew it attracted ants and a London physician named Thomas Willis deserves a major shoutout for drinking his patients’ pee to diagnose them [3]. Willis was also known to refer to diabetes as “the pissing evil”.

At this point, a diagnosis with diabetes was basically a death sentence. Without insulin around, doctors prescribed some interesting treatments to try and prolong their patient’s lives (jelly of viper’s flesh, anyone?) [4]. Harsh diets with limited calories and carbohydrates became common and sometimes patients died of starvation [5].

While Banting and Best usually get all the credit for discovering insulin, there were a few people before them that made it possible. Paul Langerhans identified pancreatic islets in 1869, and von Mering and Minkowski found that the removal of the pancreas led to diabetes in dogs in 1889. (Warning to fellow dog lovers! A lot of initial insulin research, unfortunately, involved dogs as test subjects). Two scientists named de Mayer and Schaefer both identified islet cell secretions in 1909 and 1910 respectively [6]. Prior to Banting, a few scientists including a Romanian group had already produced pancreatic extracts that lowered blood sugar levels in animals, however, these extracts were accompanied by toxic side effects and the research didn’t move forward as quickly [7].

After centuries of doom and gloom, the twenties is really when the tide started to turn for people with diabetes. In the fall of 1920, Frederick Banting was working as a surgeon in London, ON, and teaching classes. When preparing to teach a lecture about the pancreas, he read a journal article entitled “The Relation of Islets of Langerhans to Diabetes” by Moses Barron of the University of Minnesota, sparking an idea for how to extract islet cell secretions while protecting it from destruction by other pancreatic enzymes [8].

He brought his idea to J.J.R. Macleod, the head of physiology at the University of Toronto. Banting had little experience or knowledge of the field, but Macleod reluctantly agreed to give him space in his lab. Macleod also granted him the help of a senior undergraduate student research assistant, Charles Best. Best was there to help with all the chemical testing—he knew how to measure blood sugar and urine sugar levels [9].

Over the course of essentially one summer, Banting and Best, under the supervision of Macleod, developed a system for extracting islet cell secretions from dogs and administering it to pancreas-less dogs to lower their BG levels. Because it was difficult to obtain large amounts of such extract, they soon developed a new protocol for isolating whole pancreas extracts from cows [10].

In January 1922, an impure extract made by Banting and Best was administered to a 14-year-old patient named Leonard Thompson in a clinical trial. His BG levels dropped mildly, but he continued to have ketones and developed an abscess at the injection site. Macleod invited James Collip from the University of Alberta to purify the extract. In a second trial, Leonard Thompson received Collip’s purer version through daily injections and saw significant improvement. In April, the Toronto team wrote a paper announcing their discovery of insulin and its therapeutic success [11].

What I have not mentioned until now is that Banting and Macleod seriously butt heads throughout this entire process. Banting was constantly worried that Macleod was stealing credit for his work. And while Banting had undeniable enthusiasm and drive for the project, Macleod’s previous scientific expertise was necessary for execution [12]. But what about Best’s assistance? And Collip’s essential advances in purification? The 1923 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine officially ended up going to Banting and Macleod [13]. Banting almost rejected it but instead decided to share his prize money with Best, and Macleod followed suit by similarly acknowledging Collip [14]. A happy ending, eh? But the discovery of insulin is really a beginning! So, what happened next?

Manufacturing insulin at a large scale proved to be difficult. The Toronto team received an American patent on insulin and Toronto’s preparation method in 1923 for quality assurance [15]. Banting, Collip, and Best sold the patents to the University of Toronto for $1.00 each. Cue Banting’s famous words: “insulin belongs to the world, not to me” [16].

The University of Toronto also accepted an offer of collaboration from Eli Lilly and Co., an American pharmaceutical company, to aid in the manufacturing of insulin [17]. August Krogh, who was married to a woman with diabetes, visited Toronto from the University of Copenhagen and was authorized to make insulin in Scandinavia, founding Nordisk Insulin Laboratory [18]. Connaught Laboratories at the University of Toronto were responsible for making insulin in Canada. Connaught Labs expanded over the years and continued making insulin through the seventies. Through a series of acquisitions, what used to be Connaught has become a part of Sanofi [19]. The “Big Three”, Eli Lilly and Co., NovoNordisk, and Sanofi continue to control most of the world’s insulin market.

You probably aren’t surprised to hear that insulin has changed considerably since this amazing breakthrough almost 100 years ago. So how did we get from cow pancreas extracts to the bottle of Humalog, for example, sitting in your fridge?

One of the first major innovations in insulin was its crystallization. Small amounts of insulin crystals were first produced at Johns Hopkins University in 1926. This advance in crystallization laid the groundwork for the creation of the first long-acting insulin.

In Denmark, it was found that adding a molecule from fish sperm called protamine to insulin slowed its action. Connaught then added trace amounts of zinc to protamine insulin in 1939, creating a more stable and longer-lasting combination. This Protamine Zinc insulin soon became the most popular kind of insulin in Canada [20].

Next was NPH. It was first developed in Denmark in 1946 and licensed in Canada in 1950. NPH insulin acts at an intermediate speed between regular insulin and protamine zinc insulin.

Soon after in 1955, Novo Laboratories in Denmark introduced the Lente Insulin line which was also combined with zinc. One variation, Semilente, was soluble in blood and fast-acting, while Ultralente was insoluble in blood and slow-acting [21].

Up until this point, insulin was still derived from animal pancreases. This meant that a) insulin manufacturing was dependent on supply from the meatpacking industry and b) injected insulin caused some patients to have adverse immune reactions [22]. Alleviating both these problems, the first synthetic human insulin was produced in 1978. A groundbreaking moment for the biotech industry, scientists at Genentech used recombinant DNA technology to express the insulin gene in E. coli [23]. In this way, insulin could be made by bacteria instead of being extracted from animals. Eli Lilly released the first synthetic human insulin under the name “Humulin” in 1982. Vegans with diabetes, rejoice!

In 1996, Eli Lilly marketed the first analogue insulin, “Humalog” [24]. Analogue insulins are genetically modified to change how they are metabolized by the body. Other examples include NovoRapid and Lantus. There has also been growing interest in bringing more “biosimilar” insulins to market as patents expire, ideally serving as lower-cost alternatives to existing insulin products. Despite being around for so long, insulin is still unaffordable for many people living with diabetes. Introducing competition from biosimilar versions of insulin may be a way to increase accessibility.

A lot has happened in the world of insulin since the summer of 1921! As folks with diabetes, we are often looking forward to the next big thing—pumps, CGMs, bionic pancreases? islet cell transplants?! But, it is also nice to look back every once in a while. So, next time you pull out your insulin to change your infusion set or give an injection, I challenge you to remember the rich history behind it.

References:

[1] Lakhtakia, Ritu. “The history of diabetes mellitus.” Sultan Qaboos University medical journal vol. 13,3 (2013): 368-70. doi:10.12816/0003257

[2] Ritu, “The history of diabetes mellitus”

[3] Ritu, “The history of diabetes mellitus”

[4] Ritu, “The history of diabetes mellitus”

[5] “The History of a Wonderful Thing We Call Insulin.” The History of a Wonderful Thing We Call Insulin | ADA, American Diabetes Association, 1 July 2019, www.diabetes.org/blog/history-wonderful-thing-we-call-insulin.

[6] Ritu, “The history of diabetes mellitus”

[7] Louis Rosenfeld, Insulin: Discovery and Controversy, Clinical Chemistry, Volume 48, Issue 12, 1 December 2002, Pages 2270–2288, https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/48.12.2270

[8] Rosenfeld, “Insulin: Discovery and Controversy”

[9] Rosenfeld, “Insulin: Discovery and Controversy”

[10] Rosenfeld, “Insulin: Discovery and Controversy”

[11] Rosenfeld, “Insulin: Discovery and Controversy”

[12] Rosenfeld, “Insulin: Discovery and Controversy”

[13] Vecchio, Ignazio et al. “The Discovery of Insulin: An Important Milestone in the History of Medicine.” Frontiers in endocrinology vol. 9 613. 23 Oct. 2018, doi:10.3389/fendo.2018.00613

[14] Vecchio et al., “The Discovery of Insulin: An Important Milestone in the History of Medicine.”

[15] Rosenfeld, “Insulin: Discovery and Controversy”

[16] Palme, Rachel Delle. “Insulin Patent Sold for $1.” Banting House, 14 Dec. 2018, bantinghousenhsc.wordpress.com/2018/12/14/insulin-patent-sold-for-1/

[17] Rosenfeld, “Insulin: Discovery and Controversy”

[18] Rosenfeld, “Insulin: Discovery and Controversy”

[19] Rutty CJ. “Couldn’t live without it”: diabetes, the costs of innovation and the price of insulin in Canada, 1922-1984. Can Bull Med Hist. 2008;25(2):407-431. doi:10.3138/cbmh.25.2.407

[20] Rutty, “Couldn’t live without it”: diabetes, the costs of innovation and the price of insulin in Canada, 1922-1984.

[21] Rutty, “Couldn’t live without it”: diabetes, the costs of innovation and the price of insulin in Canada, 1922-1984.

[22] Rutty, “Couldn’t live without it”: diabetes, the costs of innovation and the price of insulin in Canada, 1922-1984.

[23] Editor. History of Insulin, Diabetes.co.uk, 15 Mar. 2019, www.diabetes.co.uk/insulin/history-of-insulin.html.

[24] Diabetes.co.uk, “History of Insulin”