The Firsts: Stories of the Earliest Users of Insulin: This blog post is part of a series celebrating the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin. These blogs were written by CIM intern Eleanor Medley – you can check out our last blog on the incredible Eva Saxl here!

When most people think about the discovery of insulin, the scientists come to mind. But what about the people with diabetes they first helped? What about all those on the receiving end of this discovery? Here, we will share the stories of the first few people to access insulin therapy.

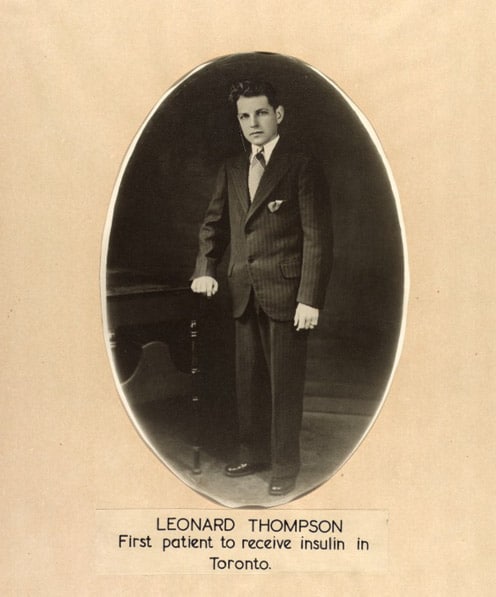

Leonard Thompson

Leonard Thompson was born in 1908 and diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes in 1919. [1] He was put on a starvation diet and admitted to Toronto General Hospital in December of 1921. At age 14, Thompson weighed only 65 lbs and was drifting in and out of a coma. [2] His father agreed for him to participate in clinical trials for Banting and Best’s experimental pancreatic extracts.

On January 11, 1922, Thompson became the first person to ever receive an insulin injection. The preparation was impure—it had little effect on his BG and resulted in an allergic reaction. [3] On January 23, he received a second set of injections that were purified by James Collip. Miraculously, his BG returned to normal and his symptoms began to disappear. [4] Word quickly spread that a diabetes treatment had been discovered.

Thompson lived for 13 more years, eventually dying of pneumonia at age 27.

“Formal Photograph of Leonard Thompson.” The Discovery and Early Development of Insulin, University of Toronto Libraries, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, Toronto, insulin.library.utoronto.ca/.

Dr. Joseph A. Gilchrist

Many think that Leonard Thompson was the first to receive exogenous insulin, but in fact, a man named Joseph A. Gilchrist participated in the very first human clinical trial. While Thompson was administered insulin via injection, Gilchrist’s first dose was oral and therefore ineffective.[6] Gilchrist was an old friend and classmate of Banting’s, diagnosed with diabetes after their graduation while training with the Canadian Army Medical Corps.[7] He later received insulin injections and started regular treatment in May 1922.[8]

While serving as a physician at Christie Street Military Hospital in Toronto, Gilchrist continued testing early insulin on himself.[9] He lived to be 58 years old.

“Photograph of Dr. Joseph Gilchrist.” The Discovery and Early Development of Insulin, University of Toronto Libraries, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, Toronto, Source: insulin.library.utoronto.ca/.

Teddy Ryder

Teddy Ryder was born in New Jersey in 1916 and diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes at the age of four.[10] At five years old, Teddy only weighed 27 lbs and his uncle asked for him to be treated in Toronto.[11] Despite having limited insulin available, Banting agreed to include Teddy in early clinical trials in July 1922.[12] He improved quickly and Banting even attended his sixth birthday party. Teddy returned home to Connecticut in October but kept in contact with Banting through letters.[13] The press referred to Ryder as Banting’s “living miracle”. He died at the age of 76 in 1993.[14]

“Photograph of Teddy Ryder, 10/07/1922.” The Discovery and Early Development of Insulin, University of Toronto Libraries, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, Toronto, Source: insulin.library.utoronto.ca/.

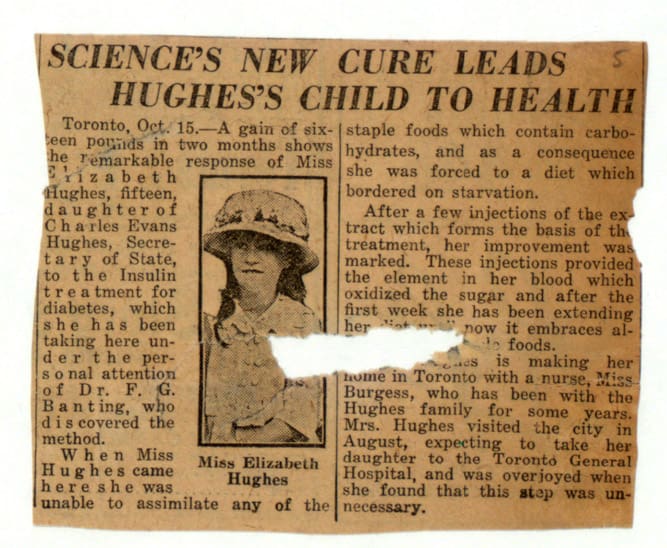

Elizabeth Hughes

Elizabeth Hughes was one of Banting’s most famous patients. She was born in 1907 in Albany, NY to the U.S. politician Charles Evans Hughes and his wife, Antoinette.[15] She was diagnosed with diabetes at age 11, and by age 14, her mother described her as “pitifully depleted and reduced”.[16] The Hughes family sent Elizabeth to Bermuda with her nurse in the winter of 1922 with hopes that the warmer climate would improve her condition, however, she came back weaker than ever.[17]

Insulin was still scarce at the time, but Banting accepted Hughes as his private patient, perhaps due to her influential family.[18] Her health improved drastically and she later went to Barnard College.[19] She married a lawyer named William Gossett and had three children.[20] As an adult, she preferred to keep her diabetes a secret, telling very few of her close friends about it.[21] She lived to be 73 years old.

“Science’s New Cure Leads Hughes’s Child to Health.” The Discovery and Early Development of Insulin, University of Toronto Libraries, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, Toronto, Source: insulin.library.utoronto.ca/.

Charlotte Clarke

Charlotte Clarke was admitted to Toronto General Hospital in July 1922 with gangrene (death of body tissue due to lack of blood flow) in one of her legs.[22] She was 57 years old and had diabetes. Her leg needed to be amputated and she received insulin injections in preparation.[23] Her surgery marked the first major operation performed on a person with diabetes with the aid of insulin.[24]

It is important to acknowledge the role of privilege in access to early insulin. In 1923, there were reports of a New York City Hospital only receiving enough insulin to treat 1% of diabetes cases in its care.[25] It also took time to scale up production so that insulin could be exported around the world. The first people to receive the lifesaving treatment were primarily white Canadians and Americans with access to healthcare. 100 years later, we still face issues regarding equitable insulin access on both a national and global scale.

References:

[1] “Leonard Thompson.” Diabetes.co.uk, 15 Jan. 2019, www.diabetes.co.uk/pioneers/leonard-thompson.html.

[2] Markel, Dr. Howard. “How a Boy Became the First to Beat Back Diabetes.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, 11 Jan. 2013, www.pbs.org/newshour/health/how-a-dying-boy-became-the-first-to-beat-diabetes.

[3] Markel, “How a Boy Became the First to Beat Back Diabetes.”

[4] “Leonard Thompson: Science Museum Group Collection.” Leonard Thompson , Science Museum Group, collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/people/cp167047/leonard-thompson.

[5] Altman, Lawrence K. “The Tumultuous Discovery of Insulin: Finally, Hidden Story is Told.” New York Times, 14 Sept. 1982, p. 1; “From a Patient’s Point of View.” The Discovery and Early Development of Insulin, University of Toronto Library, insulin.library.utoronto.ca/about/patients.

[6] Altman, “The Tumultuous Discovery of Insulin: Finally, Hidden Story is Told”

[7] “Joseph Applebe Gilchrist.” Great War Centenary Association, doingourbit.ca/profile/joseph-gilchrist.

[8] University of Toronto Library, “From a Patient’s Point of View.”

[9] University of Toronto Library, “From a Patient’s Point of View.”; Great War Centenary Association, “Joseph Applebe Gilchrist.”

[10] Palme, Rachel Delle. “The Long Life of One of Banting’s First Patients.” Banting House, 27 Sept. 2018, bantinghousenhsc.wordpress.com/2018/09/27/the-long-life-of-one-of-bantings-first-patients/.

[11] University of Toronto Library, “From a Patient’s Point of View.”

[12] Palme, “The Long Life of One of Banting’s First Patients.”

[13] University of Toronto Library, “From a Patient’s Point of View.”

[14] Palme, “The Long Life of One of Banting’s First Patients.”

[15] Zuger, Abigail. “Rediscovering the First Miracle Drug.” New York Times, 4 Oct. 2010.; “Elizabeth Hughes Gossett.” Diabetes.co.uk, 15 Jan. 2019, www.diabetes.co.uk/pioneers/elizabeth-hughes-gossett.html.

[16] Zuger, “Rediscovering the First Miracle Drug.”

[17] “Hughes (Elizabeth) Papers.” The Discovery and Early Development of Insulin, University of Toronto Libraries, insulin.library.utoronto.ca/islandora/object/insulin:hughes.

[18] Zuger, “Rediscovering the First Miracle Drug.”

[19] University of Toronto Library, “From a Patient’s Point of View.”

[20] University of Toronto Libraries, “Hughes (Elizabeth) Papers.”

[21] University of Toronto Library, “From a Patient’s Point of View.”

[22] “Notes on Mrs. Charlotte Clarke .” The Discovery and Early Development of Insulin, University of Toronto Libraries, insulin.library.utoronto.ca/islandora/object/insulin:W10007.

[23] University of Toronto Libraries, “Notes on Mrs. Charlotte Clarke .”

[24] University of Toronto Library, “From a Patient’s Point of View.”

[25] “Couldn’t Live Without It”: Diabetes, the Costs of Innovation and the Price of Insulin in Canada, 1922-1984. Christopher J. Rutty